Unconditioned Stimulus: The Basics of Classical Conditioning

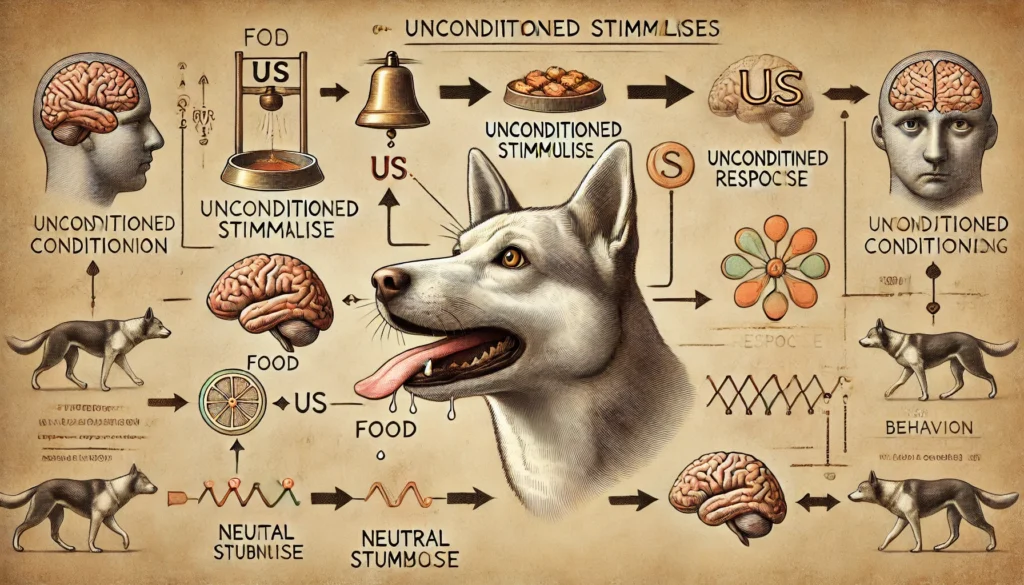

Classical conditioning, a foundational concept in psychology, describes a learning process in which a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a meaningful response. Central to this process is the unconditioned stimulus (US), a stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without prior conditioning. Understanding the role of the unconditioned stimulus is key to unraveling the mechanisms behind classical conditioning and its broader applications in behavior, learning, and therapy.

The unconditioned stimulus is crucial because it elicits a reflexive response without any prior learning. This automatic reaction is known as the unconditioned response (UR). A classic example of this is Pavlov’s experiment with dogs, where food served as the unconditioned stimulus, naturally causing the dogs to salivate (the unconditioned response). The unconditioned stimulus establishes the basis upon which other learning processes occur, laying the groundwork for associations that can lead to conditioned responses.

In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus is paired with an unconditioned stimulus, and through repeated associations, the neutral stimulus eventually becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS), eliciting a conditioned response (CR). In Pavlov’s experiment, the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus) was repeatedly paired with the presentation of food (unconditioned stimulus), leading the dogs to salivate upon hearing the bell alone (conditioned response).

This process of association has significant implications for learning and behavior. It illustrates how external stimuli can influence responses and how these associations can become deeply ingrained. The unconditioned stimulus, therefore, serves as the anchor point for classical conditioning, demonstrating how automatic reactions can be linked to seemingly unrelated cues.

Understanding the basics of classical conditioning and the role of the unconditioned stimulus provides insights into various psychological phenomena, from phobias and addictions to marketing and behavioral therapy. It reveals how associations can shape behavior, even when the original unconditioned stimulus is no longer present.

Classical Conditioning in Everyday Life

Classical conditioning isn’t confined to the laboratory; it plays a significant role in everyday life, influencing our behaviors, habits, and reactions. Advertisers, for example, use classical conditioning principles to create associations between their products and positive emotions. A catchy jingle or a celebrity endorsement (neutral stimuli) paired with a positive outcome (unconditioned stimulus) can lead to a conditioned response, such as a preference for a particular brand.

In interpersonal relationships, classical conditioning can also be observed. For instance, a person might associate a specific scent or song with a meaningful moment or loved one (unconditioned stimulus). This association can evoke strong emotions even years later, illustrating how classical conditioning can create lasting connections between stimuli and responses.

Classical conditioning also has implications for mental health. Phobias, for example, often develop through the process of classical conditioning. If a person experiences a traumatic event (unconditioned stimulus) in a particular setting or with a specific object (neutral stimulus), they may develop an intense fear (conditioned response) of that setting or object. This understanding has led to therapeutic approaches that aim to recondition or extinguish these negative associations.

Similarly, in the context of addiction, classical conditioning plays a role in reinforcing harmful behaviors. The sight of a syringe or the smell of alcohol (neutral stimuli) can trigger cravings and relapse (conditioned response) due to their previous association with drug use or drinking (unconditioned stimulus). Recognizing these associations is key to developing effective treatment strategies for addiction.

In educational settings, classical conditioning can be used to create positive associations with learning. Teachers can pair academic content (neutral stimulus) with enjoyable activities (unconditioned stimulus), leading students to develop a more positive attitude toward learning (conditioned response). This approach demonstrates the versatility and broad application of classical conditioning principles in everyday life.

Therapeutic Applications of Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning principles have been widely applied in therapeutic settings, offering effective strategies for addressing various psychological challenges. One common application is in exposure therapy, used to treat phobias and anxiety disorders. This approach involves gradually exposing individuals to the conditioned stimulus (such as a feared object or situation) without the unconditioned stimulus, to weaken or extinguish the conditioned response.

In the treatment of addiction, therapists often use classical conditioning to help clients understand and manage their triggers. By identifying the conditioned stimuli that lead to cravings, individuals can develop strategies to avoid or cope with these triggers, reducing the likelihood of relapse. This approach can involve creating new associations, where engaging in healthy activities becomes the new conditioned response instead of returning to addictive behaviors.

Classical conditioning is also used in aversion therapy, a technique that involves pairing a negative stimulus with an undesirable behavior. This approach is designed to create a conditioned response that discourages the behavior. While effective in some cases, aversion therapy is controversial and must be applied with caution and ethical considerations.

Behavioral therapies, such as systematic desensitization, use classical conditioning to reduce anxiety and promote relaxation. This method involves gradually exposing individuals to the conditioned stimulus in a controlled environment while practicing relaxation techniques. Over time, the conditioned response shifts from anxiety to relaxation, helping individuals manage their fears more effectively.

Therapists can also apply classical conditioning principles to enhance positive behaviors. Reinforcing desired behaviors with rewards or praise can create a conditioned response where individuals associate positive outcomes with certain actions, encouraging them to continue those behaviors. This approach has been effective in various therapeutic settings, from child behavior management to adult rehabilitation programs.

Online therapy platforms like Lumende provide accessible support for those seeking therapeutic applications of classical conditioning. Lumende offers a range of professional therapists specializing in classical conditioning techniques, making therapy more convenient and flexible. This online option allows individuals to explore therapeutic strategies for phobias, addiction, and other behaviors from the comfort of their homes, providing a valuable resource for those dealing with these challenges.

The Neuroscience of Classical Conditioning

The neural mechanisms underlying classical conditioning offer insights into how the brain processes and stores these associations. The hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum are key brain structures involved in classical conditioning, each contributing differently to the formation and retrieval of conditioned responses.

The hippocampus plays a significant role in episodic memory and spatial awareness, allowing the brain to form and recall associations between stimuli and responses. This region is particularly active in the initial stages of classical conditioning, where the association between the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus is established.

The amygdala, a vital structure in the brain’s limbic system, is responsible for processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety. In classical conditioning, the amygdala is heavily involved when the conditioned response has an emotional component, such as in the case of phobias. This structure helps the brain form connections between the emotional response and the conditioned stimulus, leading to heightened fear responses in some cases.

The cerebellum, primarily known for its role in motor control, is also involved in classical conditioning, particularly in the learning of reflexive or automatic responses. Studies have shown that this region is crucial for learning conditioned responses that involve motor actions, such as those seen in Pavlov’s dog experiments.

Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize, is a fundamental aspect of classical conditioning. This plasticity allows the brain to create new connections and strengthen existing ones, which is critical for the learning process. Repeated exposure to a conditioned stimulus can lead to more robust neural pathways, reinforcing the conditioned response.

Understanding the neuroscience behind classical conditioning has practical implications for therapy and rehabilitation. By identifying the specific brain regions involved in different types of conditioning, therapists can develop targeted approaches to address maladaptive responses. This knowledge also informs research into neurological disorders where classical conditioning processes may be disrupted, providing a foundation for developing new treatments and interventions.

English

English

Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français